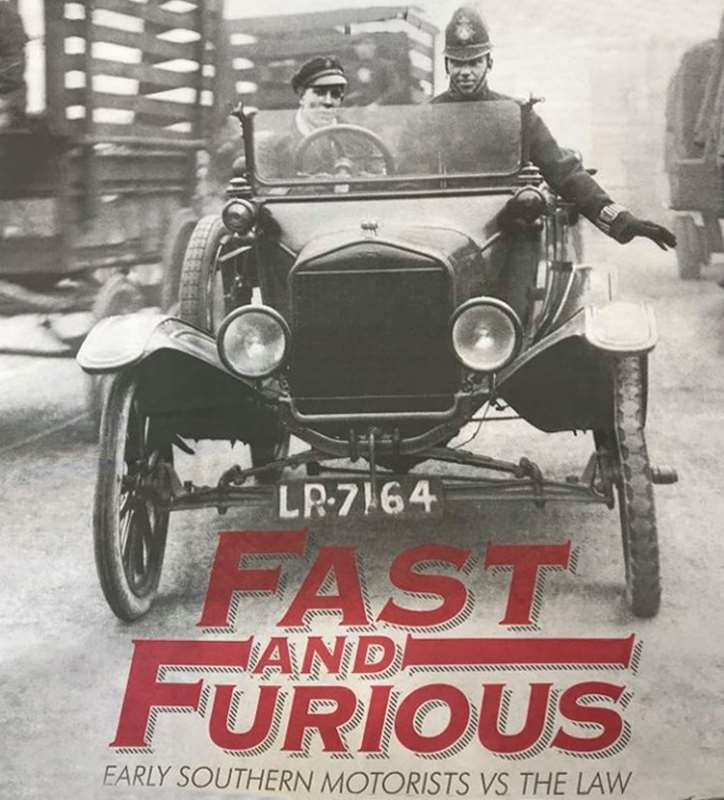

It could be the high-speed police chase. Or the tow truck in the supermarket car park.

They’re both contenders for the modern-day frontline in the long-running battle between the car and those who seek to draw some boundaries around its use.

It can be quite fraught. Take parking alone. Or the introduction of a temporary 10kmh speed limit in George St recently, to facilitate "social distancing", which had some seething. Proposed changes to Dunedin’s one-way system loom as the next flash point.

Then there’s the ongoing rumbling about the likes of speed cameras and their role in "revenue gathering".

But there’s nothing new in any of this.

The rapid development of car ownership in the first decades of the 20th century in New Zealand brought regulation and very soon thereafter friction between otherwise respectable, law-abiding citizens and those laws and regulations.

The first cars were imported to New Zealand in 1898. Their numbers grew rapidly, especially from about 1910, when there were about 3500 motor vehicles of all types, for a population of almost a million. By 1925, there were 71,403 motor cars, or one for every 17 people. A decade later the ratio had reached one to 11, one of the highest levels of car ownership worldwide.

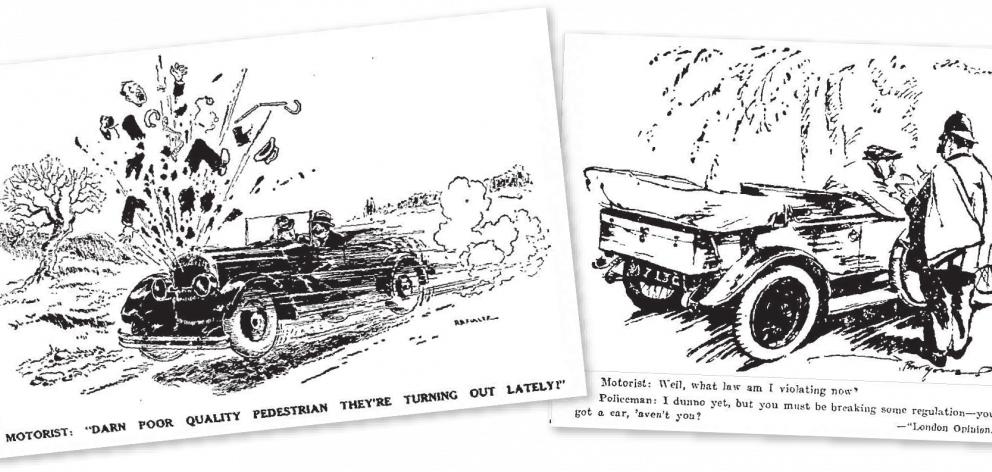

By the end of the 1920s, some of the more alarmist commentators were arguing that virtually every motorist had become a potential or actual law-breaker and this had consequences for the wider community: "The frequency with which motorists are brought before the courts for trivial offences is developing a callousness towards the law that should not prevail and there can be little wonder people are beginning to voice their protests against the nature of some of the ‘offences’ charged against them".

Parking soon became a battlefield as regulations were introduced to govern behaviour in busy city streets.

It had been long established in common law that vehicles could not be left unattended in public streets except for short periods, and in the first decades of motoring, owners of cars were required to comply. This was justified as a means of "preventing motorists using the street as a garage".

In 1909, a group of Christchurch motorists challenged the local parking regulations prohibiting the leaving of vehicles unattended for more than five minutes.

"It was unreasonable to suppose that a motor-car would get restive if left. The longer a car was left and the colder it got, the harder it was to start. It was all right to expect the driver of a horsed-vehicle to watch his animal, but it was absurd to expect a motorist to go out to see his motor-car, pat it on the bonnet, speak to it, and see that it did not run away."

In places where the local authority’s traffic inspectors rather than the police enforced the traffic regulations, they could have difficulty in exerting their authority on undeferential motorists.

One day, in 1926, the local traffic inspector approached an illegally parked car in Petone. Its owner shouted at him, "Leave the thing alone ... How dare you touch my car?"

The inspector retorted, "How dare you speak to me like that! Do you know that I am the Petone traffic inspector?".

At this, the motorist sneered, "Run away, little man, run away".

The inspector was unlucky in his choice of victim, for Captain Leopold McLaglen was "a man of exceptionally high character", or so at least the magistrate who heard his case was told.

Though that was open to question, he was "hard as nails" and "magnificently built", the self-styled jujitsu world champion and an exponent of bayonet fighting who claimed to have trained policemen and soldiers throughout the Empire. This larger-than-life character was not the sort of man to kowtow to a mere borough traffic inspector.

Local authority officials found their role greatly extended by the rapid adoption of private motor cars. Traffic inspectors, who controlled commercial horse-drawn vehicles and their drivers, found themselves also faced with a mass of unruly and sometimes incompetent amateur motor car drivers.

The police force was increasingly drawn into the role of traffic control as well. Their efforts to enforce speed regulations were particularly controversial.

When, in 1920, a lawyer defending a motorist caught in a speed trap stated he was "satisfied that the prosecuting of motorists is a money-making concern", the magistrate agreed: "I am satisfied on that point myself ... and I object to be the means of making revenue in this way."

In 1913, the Otago Witness reprinted approvingly a British complaint "that if you use the police chiefly for trapping motorists, their energies are going to be very severely curtailed in their legitimate pursuits ... We have a party of fanatical women absolutely setting the law at defiance with impunity."

These fanatics’ antipodean sisters had had the vote for 20 years by this time, and some of them were, quelle horreur, even motorists.

From the earliest years of motoring, "furious driving" was seen as a problem in need of regulation. The Motor Cars Regulation Act of 1902 stipulated that drivers should not exceed a "reasonable" speed, without specifying precisely what that speed might be. It was left to local councils to set speed limits with regard to local conditions. Lower speeds were usually specified for turning corners and busy areas. It is likely many motorists were disinclined to slow down for corners because they wished to avoid having to change gear.

Many councils redrafted their existing bylaws following the passing of the Motor Cars Regulation Act in 1906, often in consultation with motorists’ associations, which were seen as the respectable face of the new pastime.

The regulations drawn up by the Otago Motor Association, for instance, were adopted almost unchanged by three local county councils, which encouraged others to follow suit.

In Christchurch however, The Press argued that "the whole business of traffic regulation has been carried on without any real intelligence".

Even the newly instituted Department of Transport saw in 1930 that "there is a danger that regulations will be relied on more and more as a panacea for all traffic ills".

Motorists have long suspected they are seen by local authorities as easy sources of revenue. Nearly a century ago, in 1921, a motoring columnist estimated that the fines paid annually for breaches of motoring regulations came to an average of nearly five shillings per motorist (in relation to average incomes, equivalent to nearly $100 today).

"Much of this good money is ‘milked’ from the motorist for technical offences: which is a pity, for this tends to create a feeling of persecution, rather than prosecution."

For their part, local authorities pointed out that the cost of traffic control far exceeded the amount they received in fines.

By 1926, The New Zealand Herald thought "Life is growing very difficult for the motorist ... he has his days darkened and his nights made horrid by speculating on the probable form and dimensions of the licence fees and other exactions soon to be collected from him". More than 10,000 people a year were being prosecuted for motoring offences, most of them comparatively trivial. Newspapers became increasingly critical, one claiming that, in an "orgy of harsh control", the "traffic administrators in this bylaw-ridden country have lost all sense of proportion".

Setting an appropriate speed limit was a particular problem. When motoring regulations were added to the Wellington bylaws in 1907, motorcycles were restricted to 8mph (13kmh), or 4mph (6kmh) on corners. However, the regulations were "regrettably vague" with regard to cars, stipulating only that their speed be "reasonable" so as not to endanger "passengers" (that is, pedestrians).

The Canterbury Automobile Association, for its part, "considered it was better to leave the question as to what was a reasonable speed to be judged by the motorist". Some magistrates agreed, and dismissed cases on the grounds that the local bylaw setting a speed limit was unreasonable.

Speeding motorists, if caught, could be prosecuted for breaching the speed limit set by local bylaws, or under the "furious driving" provisions of the Police Offences Act of 1908.

Estimating the speed a vehicle was travelling was particularly difficult in the days when few people had any experience of motoring, and even motorists had, or affected to have, only a vague idea of how fast they were travelling.

The owner of a Wellington motor car business was charged in 1906 with "driving a motor car negligently and at a greater rate of speed than was reasonable".

A witness was asked about the speed: "I could not see the car pass me. The best definition I can give is that it went like a streak of lightning." (Laughter.)

The defendant, on oath, swore that the speed was not more than 8mph (13kmh).

Among motorists, there existed a widespread attitude that car crime was not real crime and that speeding was a mere "technical" offence. Among them was E.F.J. Grigg, of Longbeach, the son of a prominent local runholder and a notorious speedster. From 1907, he was fined repeatedly for speeding through Ashburton. Finding his already limited patience exhausted, Grigg wrote to the local paper to complain about the "frequent fining of his fellow motorists" and concluding "it is high time that we took steps to protect ourselves from this form of petty tyranny" by boycotting the town.

By the 1920s, it had become a commonplace that virtually every motorist had broken the law at some stage, wittingly or unwittingly. The bridge on the main highway at Ashburton became particularly notorious for the large number of motorists caught exceeding the 6mph (10kmh) limit, and was soon dubbed the "Bridge of Sighs".

Whatever their opinion of the speed limits, the motoring organisations were generally in favour of the testing and licensing of all drivers. Auckland and Wellington introduced practical driving tests in 1911, Christchurch in 1912, and Dunedin followed in 1915. Even then, the Auckland traffic inspector rejected "only about a dozen" of 8000 applicants for a driving licence in 1920. One of these presumably was the candidate who ran over a pedestrian during his driving test.

Some motorists felt the information required by the city council to obtain a licence was unnecessarily intrusive. In an age before the state gathered much information about its individual citizens, questions about age, height, complexion and the colour of hair and eyes could be considered "absolutely absurd".

While many car owners favoured a light touch when it came to the application of traffic regulations, they called for the full weight of the law to be brought to bear against car thieves.

Car theft had been uncommon before World War 1, when many owners felt it was unlikely because potential thieves lacked the technical knowledge to start the engine or control the vehicle once it was running.

Security was difficult to achieve with open cars, and one owner thought he had found the solution when "he chained his front wheel by means of a tremendous chain and padlock to a convenient lamp post, and returned later to find only the wheel and the chain left. Thieves had merely replaced it with the spare!"

By 1920, "joyriding" had been made a constructive theft. Because taking or the unauthorised borrowing of a car was in itself not an offence, charges were laid of stealing the petrol consumed. Car conversion finally became an offence in 1927.

The solution to the unreliability of speed estimates was the "trap" in which the police timed the passage of cars over a measured distance. Many motorists saw something underhand and unsporting in a plain-clothes policeman lurking by the roadside with a stopwatch, like "some official peeping-Tom looking through a crack in a paling fence".

It was, however, illegal for motorists or other members of the public to warn drivers of speed traps, as it counted as obstructing the work of the police. One judge drew an analogy between someone "who warned speeding motorists of a speed trap, and a suspect of murder or manslaughter who removed the dead body".

Nonetheless, motorists routinely warned each other of speed traps, an action considered "one of the good turns which promote fellowship on the highway", something that has begun to die out only in recent decades. Furious driving, however, is still with us.

- Associate Professor Alex Trapeznik teaches courses in Russian history, world history and public history at the University of Otago. Austin Gee is a Dunedin historian who edits the newsletter of the Otago Settlers’ Association.